Styling the Suburbs- An introduction to Renee Shaw

This post was originally published on my substack, which you can find here.

At 16 in early 2007, I began my first job as a sales assistant at Topshop on Sutton High Street, Greater London. While Sutton itself felt like a distinctly average place to grow up (neither quite London nor Surrey, caught in a typical suburban hinterland that seemed to lack a distinct identity as a place), Topshop felt like one of the few ‘cool’ spots on the High Street. My job at Topshop unquestionably helped nurture not only my own sense of style but also my sense of identity, introducing me to lots of new music through the mixtapes sent by head office and also helping me meet many new people outside my (very) narrow grammar school-girl world.

The Topshop on Sutton High Street disappeared during the pandemic. Today, Sutton High Street is mostly populated with cafes and phone shops, seemingly, other than sports shops, almost lacking entirely in places to buy fashionable clothes. However, Sutton, like many suburban High Streets, was once bustling and home to quite a number of independent fashion stores alongside well-known chain stores. As a historian (and formerly the curator of one of the local museums, Whitehall Historic House), I was always fascinated with the history of the High Street in my hometown and I’ve now been able to turn this into a piece of academic research.

I first became aware of Renee Shaw, a shop which was based on Sutton High Street between 1941 and 1988, back in 2014, thanks to a brief mention of the business in the fashion manufacturer Raymond Zelker’s autobiography, A Polly Peck story. Here I learnt that ‘Renee’ was the wife of Samuel Sherman, a highly successful fashion manufacturer known for his labels including Sambo Fashions and Dollyrockers. My initial research into Renee Shaw didn’t get me very far, a few photographs of the exterior of the store and the occasional press mention. However, once I began to research in further depth (and thanks in no small part to a range of wonderful people, including family members and archivists), I found not only an interesting story about one woman’s fashion boutique in suburban Surrey, but a richer story about the importance of family networks for fashion businesses.

Shared here is a small section of an article I recently had published in the Journal of Historical Research in Marketing. If you want to read the article in full, it can be accessed on my UAL research profile here https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/24328/. There’s also a version on Emerald, the journal publisher’s website, here, although there are typesetting errors in the Emerald version! https://www.emerald.com/jhrm/article/doi/10.1108/JHRM-08-2024-0062/1254692/Styling-the-suburbs-Irene-Sherman-s-dress-shops

Some background on Sutton

Sutton is the principal town of the London borough of Sutton, located on the south-western edges of Greater London. Sutton became a Greater London borough in 1965 having previously been part of Surrey. Like many suburban London towns, Sutton’s development was greatly influenced by the railway, which opened in 1847. This made the area appealing to middle-class commuters, and throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was significant suburban development in the wider borough with many middle-class villas built on the southern fringes of the town.

Tracing the Nathan family

Irene Nathan was born in 1910 in Stepney, East London. Her name appeared as ‘Rachel’ on both the 1911 and 1921 census; however, by the time she married in 1933, she was using the name Irene. Later, she used the name Renee interchangeably with Irene. As one of her shops was called Renee Shaw, I will refer to her as Irene; although in business and private life, she used both names.

Irene was the fourth child of Rebecca (nee Bernstein) and Simon Nathan, Jewish immigrants from Wilno (today part of Lithuania). Irene was one of seven children, and her siblings were also entrepreneurial figures who worked broadly in fashion and retail. Upon researching Irene’s wider family, it became clear why she chose Sutton as the location for Renee Shaw. Through electoral rolls from the 1930s and 1940s and the 1939 register, it has been possible to trace the family to various addresses in Sutton. Irene’s elder brother Bernard was already living in Sutton by 1935, and her brother Lawrence had joined him, the pair living together alongside Bernard’s wife by 1939. By 1945, Irene’s siblings Elizabeth, Gertrude (Gertie), and Ruth (Ricky) also lived in Sutton. All of Irene’s siblings lived in South Sutton, a predominantly middle-class area.

Irene’s siblings, Bernard and Gertie, both ran long-running businesses on Sutton High Street. It has not been possible to determine precisely when either business opened and neither appears in the 1932 Pile's directory of Sutton, Carshalton, Wallington & District. However, the 1938 directory indicates that ‘Bernard’s’, the ‘toilet specialist’ (a drugstore similar to Superdrug), was already established at 99 High Street. Furthermore, Maison Aimee, the hairdresser run by Irene’s sister Gertie, was already established at 183 High Street. Family members have indicated that Gertie and her husband Leonard Lennard did not establish the Maison Aimee business, but they later owned it.

In 1947, Renee’s brother-in-law Ralph King (née Rubinstein, husband of Irene’s eldest sister Ruth) also opened a retail business on the high street. His shop, located at 271 High Street, initially specialised in handbags, watches, and jewellery, before exclusively specialising in bags. While still broadly associated with the fashion trade, this was a vastly different shop to Renee Shaw, with bags, shopping carts, and suitcases displayed outside the front of the shop.

Founding Renee Shaw

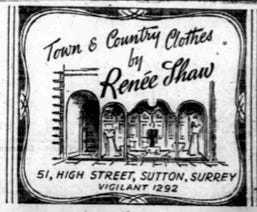

In 1941 Renee Shaw opened at 51 High Street, Sutton. There is little evidence of the business until 1946 however, when a series of advertisements were placed in local newspapers. One is shared below- I always imagined that the woman depicted in this advertisement was meant to be Irene.

In 1948 the shop was refurbished. An article in Fashion Trade Weekly (1948, p.14) suggests:

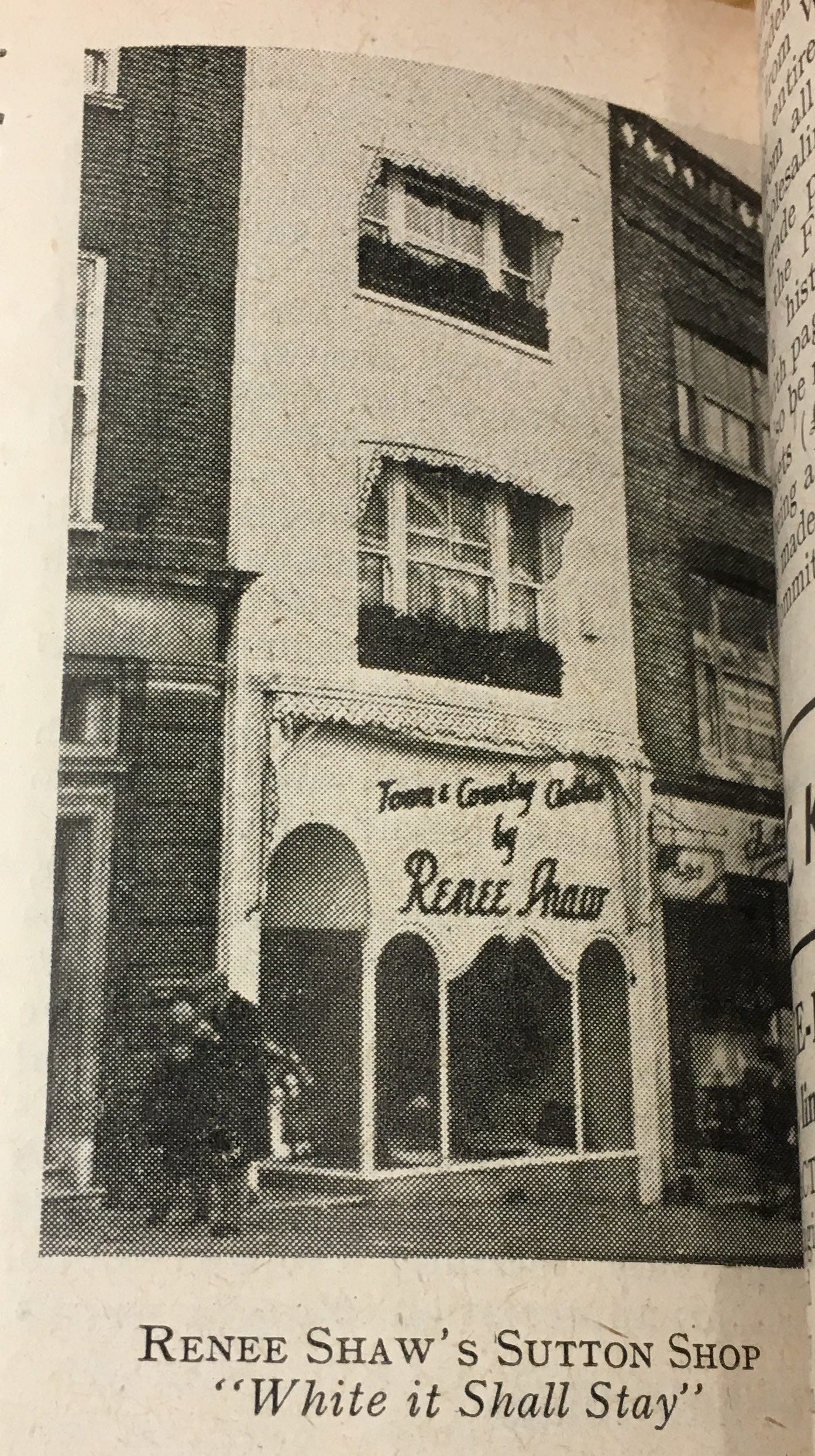

Renee Shaw completed the transformation of her fashion shop so that it got a Swiss look, complete with window boxes and fancy sunblinds. And she opened up the first floor as a Utility showroom, installing the workroom on top. It makes quite the most striking shopfront in Sutton, and Renee Shaw promises to keep it gleaming white in the Swiss tradition.

The white shopfront was undoubtedly striking, and photographs of Sutton High Street in the 1950s show that Renee Shaw was one of the only shopfronts painted white. Visually distinguishing the shop from others helped to allude to its exclusivity. The installation of a workroom on-site is also noteworthy. Alterations of ready-to-wear garments were typically offered by high-end independent dress shops in the 1940s. Having a specialist workroom on-site allowed for a better fit of garments, enhancing the exclusivity of the pieces stocked there.

Renee Shaw, 1948

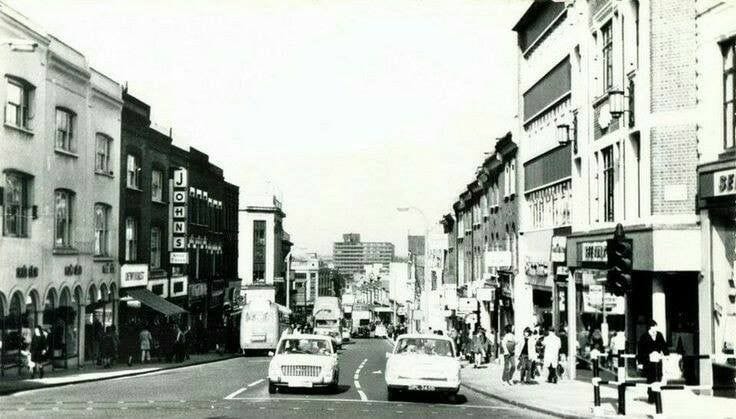

Without business records, it is difficult to gauge the store’s financial success. However, the continued expansion of the business in the 1950s and 1960s indicates a highly successful venture. In the mid-1950s, Irene took on a further unit at 55 High Street before expanding to three units at 51-55 High Street in 1960. The business expanded beyond Sutton too, with a further shop opening in Brighton in the 1960s.

Renee Shaw, 3 units on the left hand side, late 1960s.

Creating the shopping experience

Between the 1940s and 1960s, Renee Shaw endeavoured to create a veneer of luxury on the high street and an elevated shopping experience for its customers. This was achieved through carefully curated stock, distinctive store design, and attentive staffing. While, as I will later discuss, clothes at various price points were sold at Renee Shaw, customers remembered the shop as ‘posh’ and ‘classy’. The shop assistant was a vital actor in the broader network of marketing the goods at Renee Shaw, with customer recollections highlighting the highly personalised and attentive service that they provided. The expected demeanour of staff was also reflected in staff advertisements. For instance, a 1952 advertisement in the Croydon Times stated, ‘first-class experienced saleswomen required. Only those with high-class fashion experience need apply for position of first sales on model floor.’ Personalised service actively contributed to the symbolic value of the garments for sale and the perception of Renee Shaw as ‘posh’.

A fashion shop like Renee Shaw was a site for consumers to accrue and display their cultural capital. A place to see and purchase the latest fashions, but perhaps too, to be ‘seen’. Serena Dyer (2022, p.5) writes that shopping can be viewed as a ‘holistically embodied experience’. Beyond the simple act of browsing and trying on clothes, this embodied experience can be cultivated in various ways. At Renee Shaw, the experience was enriched through areas where customers could linger, such as seats for relaxation while mothers, daughters, wives and girlfriends tried on clothes. The shopping experience was further enhanced by imaginative window displays and mannequin parades, featuring some tableaux scenes created with live models in the windows themselves.

One parade, organised by Renee Shaw at Sutton Public Hall in 1953, was particularly noteworthy and made the local front-page news. This event featured couture dresses by Christian Dior, marking the ‘first’ showing of Dior’s 1953 Autumn collection in Britain, alongside garments ‘made in Renee Shaw’s workrooms’. The article does not clarify how Irene managed to procure these garments. However, what is particularly interesting is how this show acted to promote Renee Shaw. By showcasing the shop’s own garments alongside couture, it enhanced the cultural capital of Renee Shaw’s items, aligning them with Dior and suggesting that they were akin to couture.

Dior Fashion show in Sutton, 1953

Fashion at Renee Shaw

Photographs of Renee Shaw from the 1940s and 1950s show that signage was affixed to the frontage stating ‘Town and Country Clothes by Renee Shaw’ in striking cursive font. The shop’s focus on ‘town and country’ clothing was also implied in early advertisements. ‘Town and Country’ clothing can be viewed as inherently suburban, given the suburb’s ‘hybrid’ geography, one that was in close proximity to both the countryside and the city (Georgiou 2014, p.179). Rebecca Arnold (2007, p.121-123) posits that town and country wear was influenced by British men’s tailoring traditions. Originally designed for English ‘aristocratic’ sports, such as shooting and fishing, these garments were regarded as versatile, suitable for travel, and ‘smart enough’ for city wear, widely promoted as a means to ensure that a woman was appropriately dressed for all occasions. Overall, ‘town and country’ clothing suggested flexible attire suitable to the lives of middle-class women, who were Renee Shaw’s target market. ‘Town and Country’ clothing undeniably carried class-based connotations. The ‘town and country’ signage was removed around the time that Renee Shaw expanded to three retail units in 1960. This certainly reflects the changing fashion preferences of the early 1960s, as many ready-to-wear brands began shifting their production focus away from the heavier tweeds and woollens that might be associated with ‘country’ clothing.

While Irene’s shops targeted a ‘middle-class’ customer base, it is simplistic to assume that customers were exclusively middle-class. Discussing the British ready-to-wear brand Horrockses, Christine Boydell indicates that the price of garments would suggest that the ‘typical purchaser was a reasonably well-off middle-class woman’, yet interviews with women who had owned Horrockses dresses indicate that whilst some were well off, many others had to ‘scrimp and save’ to buy one (2010, p.159-161). The same can be seen with Renee Shaw, the boutique offering options for customers for whom the garments stocked may have typically been beyond their means. Regular advertisements appeared for budget accounts, allowing customers to purchase on credit (Croydon Times, 1958, p.8) and the shop also had occasional sales. As one customer remembered: ‘It was too expensive for me but they did have sales and Ms Shaw would do lay by so I was able to buy the odd thing. And we had lots of chats - she was very kind to me as an impoverished young mum who liked fashion’.

In the 1950s and 1960s Renee Shaw stocked a wide range of garments, from daywear to eveningwear, with some wedding dresses offered too. The products stocked can be traced through the many advertisements placed by the store in local newspapers across Surrey and the southern edge of Greater London and the stockist lists in leading fashion magazines. Garments sold at Renee Shaw were primarily made in Britain or Ireland and produced by brands with headquarters in London’s West End. Some American and French garments were also stocked at Renee Shaw, although these were less prevalent than the British-produced garments. To provide just one example of the wide variety of stock offered, a 1958 Croydon Times advertisement for the boutique suggested, ‘choose your spring and summer clothes from the largest selection of fashions under one roof […] Norman Hartnell, Susan Small, Brenner Sports, Sambo Fashions and other leading advertised merchandise’. The brands represented here are a broad mix – Sambo Fashions manufactured relatively low-price ready-to-wear garments. In contrast, Brenner Sports was a wholesale couture brand, producing expensive ready-to-wear, often basing their designs on French and Italian haute couture.

Advertisements and editorials highlight the wide age demographic catered to by Renee Shaw from the early 1960s. Suggestive of its older clientele, the boutique was featured as a stockist for a navy blue silk dress and jacket with a box-pleated skirt by Julian Rose, priced at £41 5s 6d, in a special 1962 ‘Mother of the Bride’ feature in The Tatler and Bystander However, at the other end of the spectrum, it is equally evident that Renee Shaw also appealed to teenage consumers. Just a month before the Tatler editorial, Renee Shaw was mentioned as a stockist in a Harper’s Bazaar ‘Young Outlook’ feature, which was specifically aimed at teenage shoppers. In this piece, Renee Shaw is listed as a stockist for a midriff-exposing two-piece outfit comprising fuchsia pink trousers and a cropped sleeveless blouse in sunset hues of pink and orange by Sambo Fashions, priced at 6 guineas.

Customer memories also corroborate the varied garments sold. One suggested, ‘My mother bought a lovely dress at Renee Shaw to wear at my wedding in 1959’ while another wrote, ‘I loved Renee Shaw and bought a lot of clothes there when I was in my teens, especially Dollyrocker dresses’. The growth of the teenage consumer was profoundly significant for fashion retailing in Britain after World War II. Illustrative of their importance, teenage girls were reported to have bought almost half of the total women's outerwear sold in 1967, disproportionately to their share in the population (Majima 2008, p.504) These consumers sought new types of garments and fresh retail establishments to purchase them from. Renee Shaw tapped into this demand while still catering to a broader customer demographic. Davison and Currie (1994, p.84), in their reminiscences of Surrey life in the 1960s, suggested:

Renee Shaw was a renegade in a High Street stodgy with outfitters and ladies’ wear retailers. It was a microcosm of what was going on in the King’s Road complete with music, eye-catching windows and assistants wearing what horrified elderly ladies looking on at the door described as pelmets round their bottoms.

This description is perhaps surprising, given the ‘Mother of the Bride’ clothes that were also stocked at Renee Shaw. In many ways, by the early 1960s, Renee Shaw’s stock represents the ‘marriage of tradition and modernity,’ which Georgiou (2014, p.179) notes was so prevalent in the twentieth-century suburb. However, it is striking that the clothes reminiscent of the fashionable zeitgeist are the ones best remembered. The comparison to ‘King’s Road’ fashion is also notable. Here, the authors effectively qualified the fashionability of Renee Shaw by comparing it to London boutiques. In the 1960s, ‘London’ carried a strong cultural capital of its own and suburban fashion stores like Renee Shaw tapped into this.

By 1960, Renee Shaw had expanded to encompass three fairly sizeable retail units. The store’s large footprint allowed for the effective establishment of mini boutiques within the shop, enabling the business to more directly target the young consumer. In 1960, an advertisement was placed in the Croydon Times seeking a ‘junior sales [assistant] for a ‘new young idea’ fashion house in Sutton, Surrey.’ The advertisement provided only a phone number rather than the shop’s name, but this was Renee Shaw. The archetypal boutique owner of the 1960s was young and fashionable, distinctly different to the madam shop owner, whom Fiona McCarthy (1965, quoted in Halbert 2022, p.103) described as ‘bridge-playing matrons with fat Pekineses’. However, shops like Renee Shaw disrupt these archetypes to an extent. Thanks to the clothes stocked, the atmosphere, the staff employed and their marketing, the store clearly presented an image to some that conveyed luxury, and to others implied edginess.

Sam Sherman and Renee Shaw

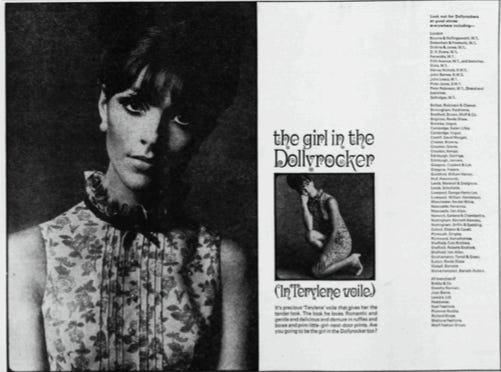

Dollyrockers advertisement showing Renee Shaw as a stockist, 1966

It is striking that in both editorials mentioning Renee Shaw and in advertisements for the shop, garments manufactured by Irene’s second husband, Sam Sherman (they married in 1941) appear more often than any other manufacturer. In addition to stocking his garments, between 1960 and 1978, Irene served as a non-executive director of Samuel Sherman Ltd., and two of her siblings were employed by the business (Samuel Sherman PLC., 1978).

Sam was born in 1910 in Soho, London, to Davis and Rebecca Sherman, Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire. He began his fashion career with Adrian Mann around 1928. In the 1930s, he joined Blanes, remaining with the company until 1947. Blanes would later become one of his direct competitors. In 1947, Sam established his own fashion manufacturing business, Samuel Sherman Ltd. The company initially employed just six staff members, with Sam acting as both director and head designer. Over the next twenty years, the business expanded significantly so by 1969, it had approximately 160 staff.

Sam initially produced garments under the now highly controversial brand name Sambo Fashions. Production focused on affordably priced cottons for young, smart women, and most of the exuberant fabric designs were exclusive to the brand. By the 1960s, Sam operated several different fashion brands under the umbrella of Samuel Sherman, catering to a broad customer base, from inexpensive ready-to-wear aimed at a teenage market to relatively costly tailored pieces. Brands included: Sambo Fashions, Dollyrockers, Super Dolls, Dolly Long Legs, Concept, Clothes by Samuel Sherman, Mr Sherman of London, Sherman Field, and Colin Glascoe.

Sam and Irene’s businesses had a symbiotic relationship and advertisements for Renee Shaw frequently featured garments from Sambo Fashions. This close connection with a manufacturing business provided Irene with intriguing opportunities, such as acquiring exclusive versions of particular garments for the store or hosting special parades to showcase new clothes. On several occasions, live models were seen in Renee Shaw’s windows wearing Sambo Fashions garments. Furthermore, it is conceivable that Renee Shaw served as a testing ground for garments, allowing new styles and brands to be tried out before a wider release, with the retail environment facilitating fast feedback on new designs.

The end of Renee Shaw

Renee Shaw closed in 1988 and was replaced by a Garfunkel’s restaurant. The closure of Renee Shaw in the 1980s reflected transformations occurring within the fashion market at large. Perhaps most significantly, many of the brands sold at Renee Shaw between the 1940s and 1970s had gone out of business by the 1980s. Furthermore, from the 1970s onwards, the car began to influence British retailing and the manner in which people shopped. Consumers increasingly moved away from high streets, engaging more with new out-of-town retail formats, particularly retail parks, enticing national chains away from town shopping centres and diminishing the high street’s significance. The changes in 1980s Sutton can be traced through telephone directories, where an increasing number of women’s fashion chains appeared alongside a decline in independent fashion boutiques. Overall, the 1980s marked the onset of a different retail experience, one that the New Economics Foundation has referred to as ‘a bland and cloned experience from street to street’ (Carmona 2022, p. 26).

Suburbs have disparagingly been seen as homogenous, yet, unquestionably in the period Renee Shaw was open for business, places like Sutton High Street were diverse, filled with a plethora of stores catering to different people. Independent fashion shops had an important role in shaping the identity of the suburb with their often-outward facing nature, for example, Renee Shaw was named in the pages of leading national magazines and newspapers, adding a degree of personality and difference to the suburb. As an independent store, Renee Shaw offered something arguably unique in Sutton. Whilst it stocked garments that could be bought elsewhere, what was significant was the atmosphere of shopping there, the retail ‘experience’, including personalised service, imaginative window displays and desirable, perhaps even aspirational, clothing.

Want to read the full article? You can find it here: https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/24328/